Wild rice, known as “manoomin” in the Anishinaabe language, is an important part of Anishinaabe culture as a staple food with spiritual and economic significance to many communities. This month’s blog explores the significance of wild rice in Anishinaabe culture and the process of harvesting and preparing it for consumption.

The Significance of Wild Rice in Anishinaabe Culture

- Cultural identity: Wild rice is deeply embedded in the cultural identity of the Anishinaabe people because it’s considered a sacred gift from Creator and is central to the Anishinaabe way of life.

- Spiritual significance: Wild rice is considered a sacred food. Its harvest is often accompanied by spiritual rituals and ceremonies. The act of gathering wild rice is seen as a way to connect the natural world with one’s spirituality. Because manoomin is believed to have its own spirit, a respectful and mindful approach to harvesting is essential.

- Nutritional value: Wild rice is a highly nutritious food source rich in vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber. It has sustained the Anishinaabe people for centuries, providing them with the essential nutrients needed for a healthy and balanced diet.

- Economic self-sufficiency: Beyond its cultural and spiritual significance, manoomin also has economic importance for the Anishinaabeg. Many Anishinaabe individuals and communities engage in cultivation, harvesting, and the sale of wild rice, providing a source of income and economic self-sufficiency.

- Connection to the land: The Anishinaabe have a deep connection to the land and water, and wild rice harvesting can be seen as an expression of this deep commitment.

- Knowledge: The process of harvesting wild rice involves a wealth of knowledge, from understanding the ideal growing conditions to using traditional techniques for hand-harvesting and processing. This knowledge is shared within the community and passed down to younger generations, contributing to the preservation of cultural heritage.

Harvesting Wild Rice (Manoomin)

Disclaimer: the harvesting process outlined below is provided as information, not as a guide to harvest wild rice. If you are interested in harvesting your own wild rice, we encourage you to bring tobacco to an elder and ask for guidance in doing so in order to respect the traditions of the Anishinaabeg.

Wild rice harvesting typically takes place from late August to early September. It’s often harvested by a crew of two or more people, as it is a communal and culturally significant activity. It’s a time for sharing stories, songs, and traditions.

Before beginning the harvest, some choose to perform a ceremony in which an offering of tobacco or food is made.

Using a birch bark canoe or a small boat, harvesters find a suitable rice bed in shallow, slow-moving waters, like lakes or rivers. The canoe or boat is paddled gently into the rice bed to avoid causing excessive disturbance.

One person gently pushes the canoe forward through the rice bed. In some traditions, this is done using a paddle, and in others a long pole. The second person uses two long wooden sticks sometimes referred to as “winnowing sticks” or “knockers” to collect the rice. One stick is used to bend and gather the rice stalks over the canoe while the other stick gently taps the rice stalks so the rice falls into and around the boat.

Collecting rice in this careful way ensures that the plant itself is not damaged and the rice that falls outside of the boat can replenish itself for next year’s harvest.

After harvesting, the wild rice is laid out to dry on a tarp in preparation for processing.

Preparing Wild Rice (Manoomin)

The Anishinaabe wild rice harvesting process involves several key steps: parching, dancing, winnowing, and finishing. Each step is integral to its harvest and preparation.

Parching

Parching involves heating the freshly harvested wild rice in a metal washtub over a fire to further dry the rice and loosen the hulls. This step ensures that all remaining moisture is removed from the rice, which will make the rice easier to extract. The person parching the rice sits with a paddle and continuously turns the rice so it doesn’t burn. This stage also imparts a distinctive roasted flavour.

Dancing

Once the rice is parched, the wild rice is traditionally processed by “dancing” on it. In this step, the rice is separated from the husks. Today, many people choose to use a wild rice husking machine called a thrasher, but traditionally, a man or boy will put on special moccasins with high cuffs that are wrapped around the ankles to prevent rice from entering. He then steps into a hole in the ground lined with canvas. Using a post for support, he tramps on the balls of his feet, moving first on one foot and then the other to loosen the husks from the rice.

Winnowing

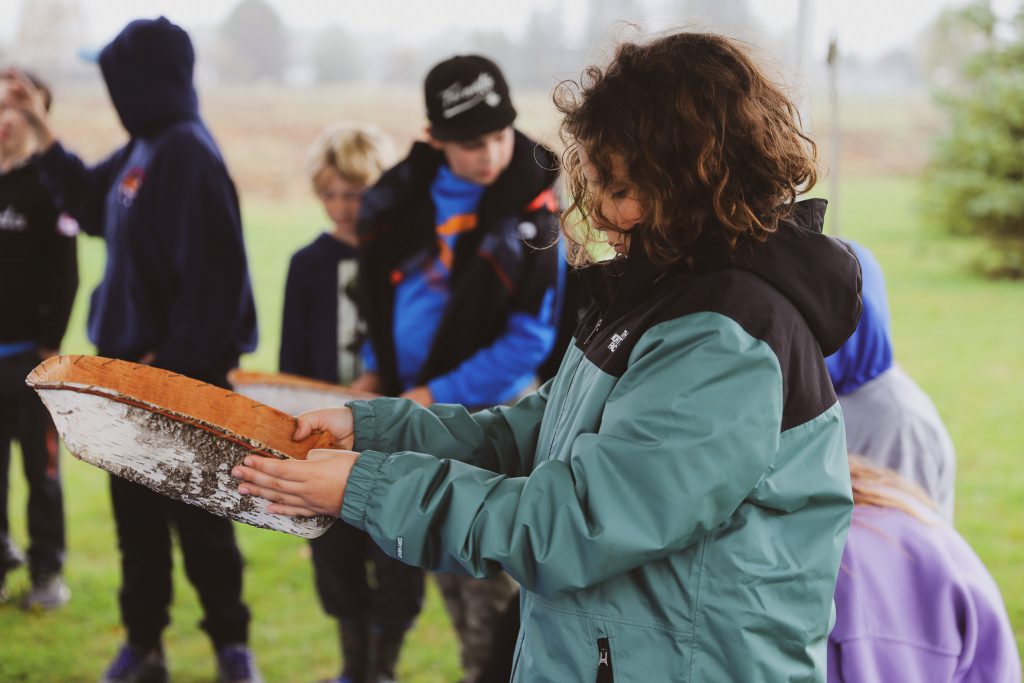

Winnowing involves separating the rice grains from the removed husks and other debris. This is typically done outdoors, where the wind aids in the separation process. Birch bark trays or shallow baskets are used to gently toss the parched rice into the air, allowing the wind to carry away the lighter husks and chaff while the heavier rice grains fall back into the container. This process is repeated until most of the husks and impurities are removed.

Finishing

The finishing step involves cleaning and sorting the wild rice to ensure it’s free from any remaining husks, debris, or foreign materials. This may involve hand-picking or using specialized screens to separate any remaining impurities. The cleaned wild rice is then ready to be stored or cooked.

Engage in culturally enriched education and events

Seven Generations Education Institute (SGEI) provides culturally enriched educational programming and events for individuals across the lifespan, including our annual Fall Harvest event (pictured above). Are you interested in learning about and celebrating Anishinaabe culture as you continue your education? Check out our upcoming post-secondary programs at https://www.7generations.org/post-secondary-programs/.